Lost Shelves 2.0

Friday, March 18, 2011

Transitioning

So, this blog was previously hosted elsewhere, but I'm bringing it back to blogger. I currently have all my old blogger posts from Demian backwards. Soon, I'll update with the 5-6 reviews I did on the outside domain. Going forward, I'd like to review and comment on all manner of things and probably ditch the ratings system.

Labels:

updates

Friday, January 29, 2010

Demian

Author: Herman Hesse

Author: Herman HesseYear: 1919

I first read Demian in college and was blown away by it. The novel is a classic example of the bildungsroman or coming of age story, that usually has as much to say about it's central character as it does about society as a whole. Hesse seems to specalize in this type of novel, since every other book I've read of his (Steppenwolf, Siddartha, Peter Camenzind) seems to follow this pattern. To his credit, however, all of these novels say radically different things and work with a nice variety of characters and settings.

Demian is not as widely known as a few of the others I mention, and I think I now understand why. A deep understanding of Jungian psychology is practically required to understand all the undercurrents of protagonist Emil Sinclair's journey from meek, put-upon youth to iconoclast mystic. While I enjoyed the early threads of Sinclair's struggles with discovering his true self and place in the world, later episodes of magical realism fell flat to me. The mystery of Demian's power and influence is never properly accounted for, and the book seems to sputter out rather than reach a grand conclsion (a la Siddartha).

With that said, though, Hesse's novel is stuffed with psychological dilemnas to ponder over. And for about 2/3 of the book, he also recounts some compelling events. Though the ending left me cold from a dramatic standpoint, Hesse's prediction of the birth of the modern mind with the beginning of World War I seems relevant and prescient today.

Rating: Brass

Labels:

book reviews

Sunday, August 16, 2009

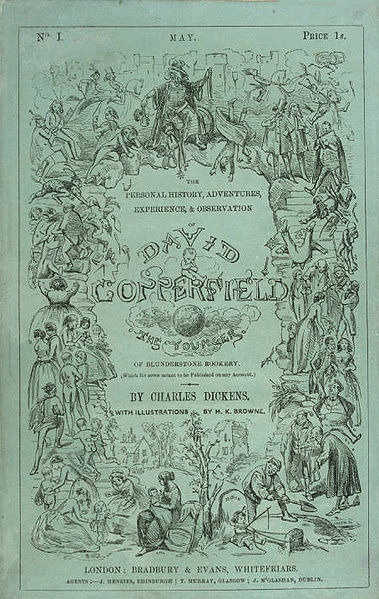

David Copperfield

Author: Charles Dickens

Author: Charles DickensYear: 1850

Having struggled through several other Dickens novels, I decided to give David Copperfield a try. It is rumored to be his greatest work (along with Great Expectations, which was a bit disappointing, to me at least) so I was hoping it might possess something that elevated it among the others. Well, within the first chapter of the 800+ page novel, I found that the rumors were true. David Copperfield is a complete masterpiece. Beginning with the night of his birth and ending several decades later, this epic novel is a perfect example of Dickens' hearty sense of humor, deep pathos for his characters, and strong outrage against the injustices of modern life. Unlike other Dickens novels, the meandering sideplots only deepen the novel and create a world where every character's life tells a fascinating story.

Readers more used to modern conventions of realism and frank storytelling may be a bit put off by Dickens' whimsical characterizations and use of staggering coincidence. But these were very common in his time, when novels were published in monthly or weekly serial installments. The use of coincidence can be a exaggerated at times, but Dickens uses it more tastefully here than in previous novels (Oliver Twist and Great Expectations spring to mind). And it is always used to enhance the drama of the individual stories, giving them deeply ironic twists that could never occur when simply reciting things as they would probably occur. Similarly, the intense villainy of Uriah Heep, the naive pompousness of Wilkins Micawber, and the angelic goodness of Agnes Wickfield (to name a few) may seem exaggerated and one-dimensional, but nonetheless these characters greatly enhance the narrative and stand as some of the most unique individuals in literature.

There are so many incredible events over the course of the novel, that I am reluctant to give anything away. So I'll leave you with the memorable opening line to hopefully whet your appetite: "Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anyone else, these pages must show."

Value: Gold

Labels:

book reviews

Wednesday, September 10, 2008

The Sun Also Rises

Author: Ernest Hemingway

Author: Ernest HemingwayYear: 1926

Hemingway's first novel used to be my one of my all-time favorite reads. There was something about the directionless plot, exotic locales, and matter-of-fact dialogue that struck me as wholly fresh and liberating. Coming back to the novel several years later, I can still appreciate those elements, but I've come to realize the truth of the cliche that "Hemingway's true genius is in his short stories." Though characters like war-scarred Jake Barnes and tragically romantic Robert Cohn are interesting, their private dramas begin to burn out after even a slender 250 page novel.

Perhaps most frustrating about the novel is Hemingway's choice of subject matter. The group of men and women he depicts are mostly wealthy expatriates whose ennui and irreverence are hard to relate with. The most earnest and sympathetic character is Barnes, though even his struggles occasionally lapse into the realm of self-pitying despair. The best line in the whole novel is delivered by him during an all-night session of insomniac pondering: "I did not care what it is all about. All I wanted to know was how to live in it." And for the most part, the novel reflects this philosophy, showing Barnes' attempts to appreciate the beauty of his surroundings despite the shenanigans of his peers and the agony of his handicap.

The Sun Also Rises still holds up as a classic, perhaps a work of a young author meant to be enjoyed by men and women still in their youth. Though seeming to profess a viewpoint of disillusionment, Hemingway's novel revels in its illusions of European decadence and wild lives free from the concerns of consequence.

Value: Silver

Labels:

book reviews

Monday, July 21, 2008

Tender is the Night

Author: F. Scott Fitzgerald

Author: F. Scott FitzgeraldYear: 1934

It’s hard to read Tender Is the Night without paralleling it to The Great Gatsby as well as Fitzgerald’s personal life. In a sense, this novel is another account of the eventual frustration and defeat of the American dream. Unfortunately, it does not dazzle in the same way that Gatsby does, and while the writing is solid and the plot compelling, Tender Is the Night falls far short of achieving the same level of transcendence.

The novel begins with an interesting bit of misdirection, placing the reader in the shoes of young starlet Rosemary Hoyt as she meets the true main characters, Dick and Nicole Diver. Dick Diver is a supreme example of American promise, but despite all his intelligence and privilege, his story ends much like that of Jay Gatsby. The relationship between the Divers (clearly echoing many aspects of Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda) is at times heartbreaking and exhilarating, but most often seems like a detached clinical study. I suppose this treatment may be an intended reflection of the Divers’ own detachment, but it manages to make the novel frustratingly distant in many sections. Most compelling is the subtly changing dynamic of the couple: through the course of the novel we see Nicole’s slow recovery while witnessing a parallel regression in Dick. It is as if her well-being is necessitated upon his gradual destruction.

There are a few scattered moments of striking beauty and insight, like when Dick, with extraordinary self-perception, muses, “The strongest guard is placed at the gateway to nothing. . . . Maybe because the condition of emptiness is too shameful to be divulged.” Also, the ending notes possess a somber grace lacking in the rest of the novel, that one almost wants to begin again and re-experience the journey in a new light. But on the whole, the poetic encapsulation of American history and culture that is so prevalent in The Great Gatsby is woefully underrepresented here, leaving us with only another sad tale of the Lost Generation.

The novel begins with an interesting bit of misdirection, placing the reader in the shoes of young starlet Rosemary Hoyt as she meets the true main characters, Dick and Nicole Diver. Dick Diver is a supreme example of American promise, but despite all his intelligence and privilege, his story ends much like that of Jay Gatsby. The relationship between the Divers (clearly echoing many aspects of Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda) is at times heartbreaking and exhilarating, but most often seems like a detached clinical study. I suppose this treatment may be an intended reflection of the Divers’ own detachment, but it manages to make the novel frustratingly distant in many sections. Most compelling is the subtly changing dynamic of the couple: through the course of the novel we see Nicole’s slow recovery while witnessing a parallel regression in Dick. It is as if her well-being is necessitated upon his gradual destruction.

There are a few scattered moments of striking beauty and insight, like when Dick, with extraordinary self-perception, muses, “The strongest guard is placed at the gateway to nothing. . . . Maybe because the condition of emptiness is too shameful to be divulged.” Also, the ending notes possess a somber grace lacking in the rest of the novel, that one almost wants to begin again and re-experience the journey in a new light. But on the whole, the poetic encapsulation of American history and culture that is so prevalent in The Great Gatsby is woefully underrepresented here, leaving us with only another sad tale of the Lost Generation.

Value: Iron

Labels:

book reviews

An Explanation of the Ratings System

Ratings on this site range from Gold (highest) to Plastic (lowest) with several stages in between. These descriptions are loosely based on The Four Ages of Man. I'm very stingy with awarding a Gold ranking, and hopefully will never have to read through an entire Plastic. Most novels will fall in between, but even the Irons have a lot to appreciate. Here is a brief breakdown of their comparative worth:

Gold [90-100%]: A true classic, universally recommended.

Silver [80-90%]: A stunning book, with just a few flaws that prevent it from being perfect.

Brass [70-80%]: Highly worthwhile, but recommended largely to fans of the genre and/or the author.

Iron [60-70%]: Flawed enough to warrant only a tentative recommendation, but not without merit.

Plastic [0-60%]: Best left on the shelf.

Gold [90-100%]: A true classic, universally recommended.

Silver [80-90%]: A stunning book, with just a few flaws that prevent it from being perfect.

Brass [70-80%]: Highly worthwhile, but recommended largely to fans of the genre and/or the author.

Iron [60-70%]: Flawed enough to warrant only a tentative recommendation, but not without merit.

Plastic [0-60%]: Best left on the shelf.

Labels:

Feature

Monday, July 7, 2008

Nine Stories

Author: J.D. Salinger

Author: J.D. SalingerYear: 1953

Despite having only four books available for purchase, Salinger is a legend among writers. There is something about his work that inspires obsession. Widely praised for The Catcher in the Rye, he is more fanatically followed by devotees of the pieced-together Glass Family stories. But what is it about his humble prose and simple (or non-existent) plots that garners so much attention? Nine Stories is book-ended by two pieces steeped in mystery. These stories, “A Perfect Day for Bananafish” and “Teddy” are simultaneously exuberant and despairingly haunted. They describe events with clear surface drama, but underneath swarm layers, if not worlds, of gloomy implication and wonderment. Perhaps you can tell that I don’t want to divulge too much detail…

In between you get a rather hit-or-miss assortment. The middle of the collection features the best stories: “The Laughing Man” is a bittersweet account of a “Comanche Club” youth group and their yarn-spinning counselor; “Down at the Dinghy” is a simple and touching account of a mother and her son; and “For Esme – With Love and Squalor” is Salinger’s brief epic of a soldier’s meeting with a precocious thirteen-year old days before shipping off for the Normandy Invasion. Unfortunately, these stellar tales (along with the hilarious “De Daumier-Smith’s Blue Period”) are balanced with pointless disinterested pieces like “Pretty Mouth and Green My Eyes.”

As usual, Salinger’s primary focus is the meeting of adolescence and adulthood; nearly every story in the collection focuses on these contrasting viewpoints. Once again, the two bookend stories provide the keenest insight into Salinger’s ideas on the matter. In “Bananafish,” Seymour Glass tells his young companion a quirky story about a peculiar fish that retreats into its undersea cave, then eats too many bananas and gets too fat to ever come out again. A metaphor for the loss of freedom and innocence upon the entrance into adulthood, Salinger expands upon this theme in “Teddy” where the titular character theorizes that the only way for people to return to their original state of being is to “vomit up” as much of the apple of original sin (in Teddy’s view, this represents reason and logic) as possible. For Salinger fans, this collection is a must-read (especially since two of the stories deal directly with Glass Family members, while a third makes extensive reference to one). Even for Holden Caulfield haters, these should be enough honesty and beauty in these stories to make the short read highly worthwhile.

In between you get a rather hit-or-miss assortment. The middle of the collection features the best stories: “The Laughing Man” is a bittersweet account of a “Comanche Club” youth group and their yarn-spinning counselor; “Down at the Dinghy” is a simple and touching account of a mother and her son; and “For Esme – With Love and Squalor” is Salinger’s brief epic of a soldier’s meeting with a precocious thirteen-year old days before shipping off for the Normandy Invasion. Unfortunately, these stellar tales (along with the hilarious “De Daumier-Smith’s Blue Period”) are balanced with pointless disinterested pieces like “Pretty Mouth and Green My Eyes.”

As usual, Salinger’s primary focus is the meeting of adolescence and adulthood; nearly every story in the collection focuses on these contrasting viewpoints. Once again, the two bookend stories provide the keenest insight into Salinger’s ideas on the matter. In “Bananafish,” Seymour Glass tells his young companion a quirky story about a peculiar fish that retreats into its undersea cave, then eats too many bananas and gets too fat to ever come out again. A metaphor for the loss of freedom and innocence upon the entrance into adulthood, Salinger expands upon this theme in “Teddy” where the titular character theorizes that the only way for people to return to their original state of being is to “vomit up” as much of the apple of original sin (in Teddy’s view, this represents reason and logic) as possible. For Salinger fans, this collection is a must-read (especially since two of the stories deal directly with Glass Family members, while a third makes extensive reference to one). Even for Holden Caulfield haters, these should be enough honesty and beauty in these stories to make the short read highly worthwhile.

Value: Brass

Labels:

book reviews

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)